1) The legendary Denarius. One of the longest-running coin denominations of all time, the Denarius started out about 200 B.C. and continued through until the reign of Gordian III in the mid-200's. Although re-tariffed at a different value, the Denarius would be reborn in the Argenteus and then the Siliqua until the final fall of Rome.

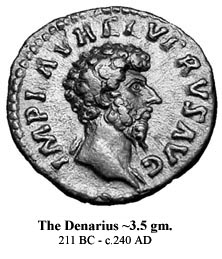

1) The legendary Denarius. One of the longest-running coin denominations of all time, the Denarius started out about 200 B.C. and continued through until the reign of Gordian III in the mid-200's. Although re-tariffed at a different value, the Denarius would be reborn in the Argenteus and then the Siliqua until the final fall of Rome.It is rare to find Denarii, or any other silver denomination for that matter, in groups of uncleaned coins such as came with this kit. However, unlike gold, silver does tarnish in dirt given enough time and/or appropriate soil conditions. For this reason, you may occasionally stumble upon a Denarius and no matter how worn it is always a welcome sight and cause for celebration. Because during the time the Denarius was in vogue it coincided with the Roman empire's greatest military and economic might, the portraits of the various emperors were rendered in excruciatingly lifelike detail. In fact, the portraits are so realistic that one can literally track the aging of several emperors who held their title long enough. All facial features including defects, wrinkles and so on were captured by the skilled engravers. What this means to you is that it should be relatively easy to identify the emperor based simply on matching the portrait to other coins which have already been attributed. If the lettering is clear in most cases the emperor's name will stand out immediately.

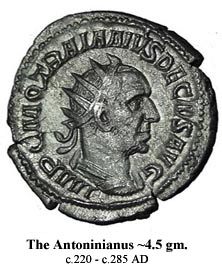

2) As the economy and heyday of the Roman empire began its decline, the Denarius was slowly phased out in favor of a slightly larger silver coin whose name as given by the Romans has so far eluded numismatic historians. We simply call them the Antoninianus or "double Denarius". In the beginning the Roman authorities insisted that one of these Antoniniani were to be worth two Denarii despite the fact that the average silver weight of the coin went up only about a gram to ~4.5 grams. For all intents and purposes they looked the same. To distinguish the old from the new, it was decided that the emperors would wear a radiate crown representing sun rays in association of the god Sol, the foremost deity.

2) As the economy and heyday of the Roman empire began its decline, the Denarius was slowly phased out in favor of a slightly larger silver coin whose name as given by the Romans has so far eluded numismatic historians. We simply call them the Antoninianus or "double Denarius". In the beginning the Roman authorities insisted that one of these Antoniniani were to be worth two Denarii despite the fact that the average silver weight of the coin went up only about a gram to ~4.5 grams. For all intents and purposes they looked the same. To distinguish the old from the new, it was decided that the emperors would wear a radiate crown representing sun rays in association of the god Sol, the foremost deity.The initial plan of officially valuing the new Antoninianus at double the Denarius made a bad situation worse for the State treasury. Roman citizens were not duped and it appears that they simply weighed the coins at the marketplace and reverted to trading them as bullion. Losing faith in the official economic plan escalated an unprecedented bout of inflation. In order to meet its debts at the same time it was faced with a precious metal shortage the hapless administrators could do nothing about except mint cheaper coins. And to make a silver coin cheap all you need to do is take the silver out. This, of course, precipitated a vicious cycle that nearly bankrupted the treasury and is today considered one of the principal reasons for the eventual downfall of the empire two centuries later.

If silver Denarii are hard to come by in uncleaned condition this is only that much more so for silver Antoniniani which, due to being bigger and having been minted for a much shorter span of time, are almost never found. However, as the gradual debasing of coins began in earnest in the mid-third century, the coins themselves became nearly worthless and their loss would have been no great grief. For this reason, one often comes across radiate Antoniniani that once had a silver sheen but whose core is a coppery alloy. The silver wash, however, was very thin and fragile and fully silvered coins from this era are hard to come by. It is occasionally possible to find an uncleaned specimen which has some traces of this silvering left.

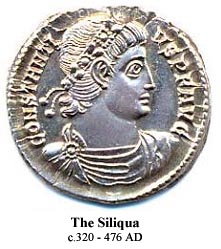

3) The emperor Diocletian inherited a chaotic empire which was being besieged from within by civil wars and by foreign nations alike. In order to reverse this sorry condition he enacted several visionary reforms which were to have a lasting impact on the empire. One of these reforms was a complete overhaul of the coinage system. He had the mints coordinate with one another so that the designs and weights of the various coins would match and thus be consistent throughout the empire. Along the way he abandoned the failed Antoninianus but was unable to revive the Denarius because of a severe shortage of silver. Instead, he initiated the Follis which was still a copper coin at heart but now attached to it the incredible valuation of 25 Denarii to one of the new Folles. Naturally, no one was very amused but what could they do?

3) The emperor Diocletian inherited a chaotic empire which was being besieged from within by civil wars and by foreign nations alike. In order to reverse this sorry condition he enacted several visionary reforms which were to have a lasting impact on the empire. One of these reforms was a complete overhaul of the coinage system. He had the mints coordinate with one another so that the designs and weights of the various coins would match and thus be consistent throughout the empire. Along the way he abandoned the failed Antoninianus but was unable to revive the Denarius because of a severe shortage of silver. Instead, he initiated the Follis which was still a copper coin at heart but now attached to it the incredible valuation of 25 Denarii to one of the new Folles. Naturally, no one was very amused but what could they do? True silver coins were produced but in very limited quantities for special occasions or during the rare periods when silver was plentiful. The Argenteus, Siliqua, Miliarenses and related fractions are all rare denominations you have no reasonable hope of finding in uncleaned form. Rarest of the silver issues are oddly large medallions minted at the very end of the empire under the obscure emperor Priscus Attalus. These mammoth medallions weighed up to 80 grams, or about 20 Denarii, and might have traded as the equivalents of a gold Solidus. Needless to say, these are exceedingly rare.